We tend to think we know best. But, how much more effective could we be if we understood the deeper values that drive others?

As individuals, as families, as workers, as cities, and as a nation, empathy is the gateway to profound progress.

I AM RIGHT

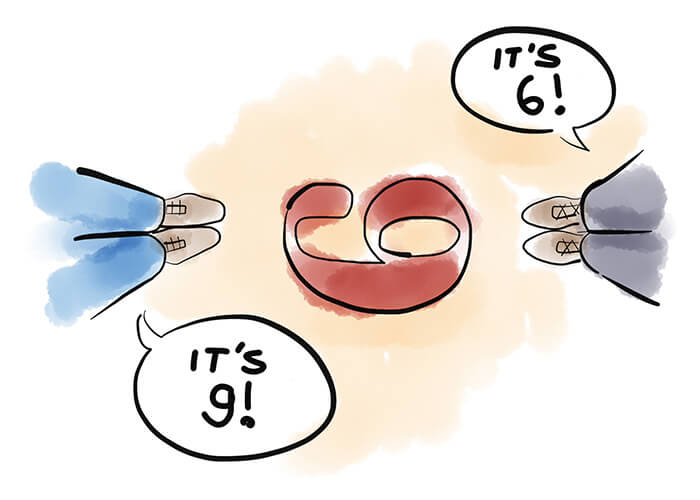

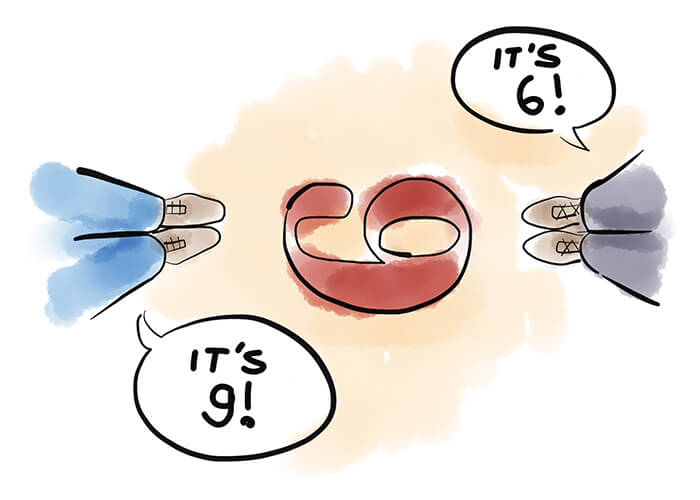

We all want to be knowledgeable. We want to be trustworthy. And we want to be right. It’s in our nature. We formulate opinions about how life should be based off of the experience we’ve personally had. Makes sense. “Everything I’ve been through has helped me get to where I am today,” we tell ourselves, “so it must work.” It’s not a far jump from that, then, to “therefore, I am right in how and what I think.” This, in a word, is your perspective.

THE WALL

But majority of the time, that method of thinking resembles an unwelcoming impediment to progress: a wall. By slamming our flags into the ground and figuratively shouting, “This is how it is and should be!” we discourage effective communication and opportunities for growth. Sure, your perspective is what has gotten you this far in life (congrats on that). But, being unwilling to empathize with other points-of-view leaves you at a giant disadvantage – you’re leaving opportunity just lying on the table! Just because you love red, and someone that sits down next to you loves blue, doesn’t mean you don’t have anything else in common that – if brought out through empathetic discussion – could mean massive mutual success. So…

BECOME A COLLECTOR

A skill that is often taught in leadership studies ought to be one of your own, regardless if you have a desire to be a leader of any kind. What skill are we talking about? Empathy. Or, “collecting perspective.” As Steffan Surdek, a Consulting Principal, Corporate Trainer, and Integral Coach at Pyxis Technologies explains, “The skill is about reaching out to people and better understanding their point of view on a specific topic or situation. It is about being truly and authentically curious about hearing and learning more about their perspective.” Now, this doesn’t mean that you have to suddenly subscribe to these new perspectives. As Robert Mnookin says in his book Beyond Winning: Negotiating to Create Value in Deals and Disputes, “empathy does not require people to have sympathy for another’s plight – to ‘feel their pain.’ Nor is empathy about being nice… Empathizing with someone, therefore, does not mean agreeing with or even necessarily liking the other side.” Instead, it is simply understanding and respecting the other side.

For example, I think guns and gun sales in America should be highly regulated. Owning a gun should be more arduous a process than owning a car, to ensure firearms are not being granted to folks unfit to own and operate them. However, I know there are millions of proud gun owners whose temper is immediately triggered by reading that perspective because they flat-out disagree with it. In fact, some might hate me for it. In a millisecond, they categorize me in a word: “enemy.” “This guy wants to take my guns away! Must be a libtard snowflake from the west coast who’s never held a gun in his life. Doesn’t know what the f*** he’s talking about,” they’ll passionately say. All this without even having met me or discussed the issue with me to find out more information. If only I were asked about what makes me think what I think, I’d start off with a piece of information to build common ground. Like the fact that I own two guns myself and was taught skeet and trap shooting by an Olympic gold-medalist instructor, when I was in high school. “See,” I would say, “we’re not as different as you might think.”

DIG DEEPER

To keep things simple, let’s continue with the example of the gun ownership debate. Why do I really want guns to be more regulated? Simple truth: I don’t want my friends and family to die because of them. Humans are emotional beings, and crimes of passion, misjudgment, and those committed while under the influence are a real thing (no need to list the myriad examples, I think). Remove a lethal weapon like a gun from the hands of an emotional being, and fatality rates plummet. Remember: that is my opinion – my perspective.

That being said, it’s now my turn to ask my pro-gun counterpart what she thinks. Let’s call her Amy. I ask her, “what makes you care about guns so much?” Notice I didn’t ask, “why are you against gun reform?” Asking questions framed in opposition rarely lead anywhere positive. Instead, I asked a question framed in affection that targets the emotional center of my counterpart, which further aims to change our argument into a discussion. She might go on to explain that guns have been part of her family for a long time (tradition), and that her dad always took her out hunting as a kid (guns therefore symbolize love to her), and she’s proud of the relationship she has with her father and the family she’s built (she now owns guns of her own and has taught her children to hunt). She might go on to also explain that from where she comes, you’re taught that it’s okay to protect yourself and your family from harm with lethal force, and that the right to do so is as normal as the right to buy groceries. “It’s been my normal since the day I was born,” she says.

Even if I disagree with what Amy’s told me, even if I think it’s absolutely insane, I must respect it. It is her truth. And as long as I communicate and demonstrate that kind of respect, I ensure the greatest odds that Amy will do the same for me. Because in the end…

IT ALL COMES DOWN TO EMOTION

All of our perspectives anchor themselves in our emotions. The more passionate we are about them, the more deeply-rooted in our subconscious they are. Amy’s fiery spirit about relaxed gun ownership laws lies anchored in her love for her father. My ardent longing for increased gun control roots itself in my love for my family and friends. So in the end, we – like most every other human being ever – both formed perspectives that stem from a common foundation: love. All humans can empathize with love. And patience and maturity are vital to effectively discussing important issues, if there’s any hope for progress.

In his best-selling book Never Split The Difference, Chris Voss, former head of the FBI’s International Hostage Negotiation Team, explains just how much emotion plays a role in the decisions we make and the actions we take. The wisdom he imparts apply not just to hostage negotiation, but to anyone longing to become a more effective thinker, speaker, and doer. “Once people get upset at one another, rational thinking goes out the window,” Voss says. To use an excerpt from his book, here’s an example of how core values and emotions lie at the heart of what formulates our perspectives, and how empathizing with other’s can lead to progress:

It was 1998 and I was standing in a narrow hallway outside an apartment on the twenty-seventh floor of a high-rise in Harlem. I was the head of the New York City FBI Crisis Negotiation Team, and that day I was the primary negotiator. The investigative squad had reported that at least three heavily armed fugitives were holed up inside. Several days earlier the fugitives had used automatic weapons in a shoot-out with a rival gang, so the New York City FBI SWAT team was arrayed behind me, and our snipers were on nearby rooftops with rifles trained on the apartment windows.

Until recently, most academics and researchers completely ignored the role of emotion in negotiation. Emotions were just an obstacle to a good outcome, they said. “Separate the people from the problem” was the common refrain.

But think about that: How can you separate people from the problem when their emotions are the problem? Especially when they are scared people with guns. Emotions are one of the main things that derail communication. Once people get upset at one another, rational thinking goes out the window.

Emotions aren’t the obstacle, they are the means.

Getting to this level of emotional intelligence demands opening up your senses, talking less, and listening more. You can learn almost everything you need – and a lot more than other people would like you to know – simply by watching and listening., keeping your eyes peeled and your ears open, and your mouth shut.

We had one big problem that day in Harlem: no telephone number to call into the apartment. So for six straight hours, relieved periodically by two FBI agents who were learning crisis negotiation, I spoke through the apartment window. I didn’t give orders, or ask what the fugitives wanted.

Instead, I imagined myself in their place. “It looks like you don’t want to come out,” I said repeatedly. “It seems like you worry that if you open the door, we’ll come in with guns blazing. It looks like you don’t want to go back to jail.”

For six hours, no response.

And then, when we were almost completely convinced that no one was inside, a sniper on an adjacent building radioed that he saw one of the curtains in the apartment move.

The front door of the apartment slowly opened. A woman emerged with her hands in front of her.

I continued talking. All three fugitives came out. None of them said a word until we had them in handcuffs.

Then I asked them the question that was most nagging me: Why did they come out after six hours of radio silence? Why did they finally give in?

All three gave me the same answer: “We didn’t want to get caught or get shot, but you calmed us down… we finally believed you wouldn’t go away, so we just came out.”

There is nothing more frustrating or disruptive to any negotiation than to get the feeling you are talking to someone who isn’t listening. Ignoring the other party’s position only builds up frustration and makes them less likely to do what you want.

So before you shout from the rooftops that you’re right, go seek out some perspectives that are different than yours. Think outside your box. They just might open your mind to new solutions, relationships, and opportunities you never thought possible, beforehand.